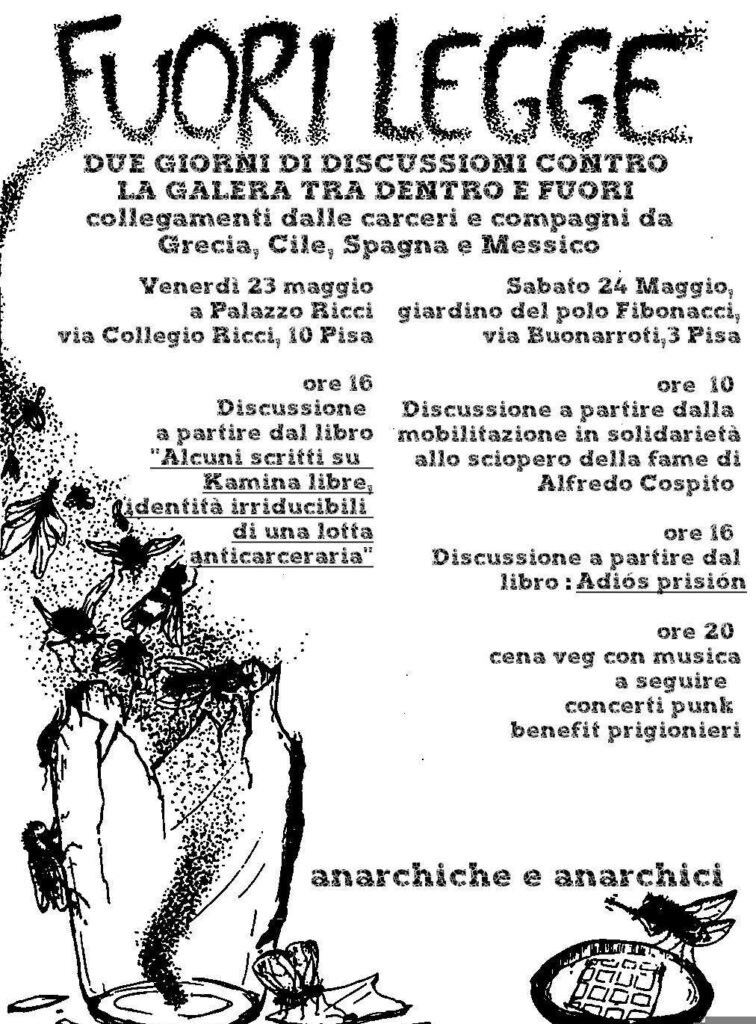

Two days of discussions against prison, inside and outside.

On the night of Wednesday, April 13, a wave of arson attacks across Paris and southern France targeted prison police and the system surrounding incarceration. This news from across the Alps arrived about a month after the opening of a new isolation regime, inspired by Italy’s 41 bis, recently introduced in France by Justice Minister Darmanin.

As states rearm and consequently tighten their ranks on the domestic front, and as new developments in capitalism dictate the progressive reduction of the welfare state and its function of resolving conflicts, incarceration assumes an even more fundamental role in managing “human excesses” that, for one reason or another, are now expelled from the production cycle and impossible to reintegrate. Populations must be kept in order and discipline to force them to accept the material and ethical costs of war and to make them participants in the regular functioning of the war and state machine. The State is war, and it is first and foremost at war against “its own” exploited. Individuals useless to the needs of armies and exceeding the demands of production are progressively kept under control through virtual alienation, economic blackmail, but above all through the increase in coercive force, hence, for example, the constant growth of the incarcerated population. Here, the true face of prison is revealed as an integral and fundamental part of the mechanisms of oppression and exploitation. The experience of incarceration in this society can become a common experience for every individual, a highly probable dimension within a life from whose misery there is no way out except by attempting the path of illegality, thus risking “the unexpected of prison”: this suffering without absolution can lead to self-destruction as much as to the path of revolt for those who have nothing to lose but their chains.

“Prison is the most brutal and immediate expression of power, and like power, it must be destroyed; it cannot be progressively abolished. Those who think they can improve it and then destroy it remain its prisoners forever.”¹

INSIDE AND OUTSIDE

Drawing from the texts Adíos Prisíon and Kamina Libre, which discuss specific experiences and visions, we want to look at a recent and still living past, where a multi-voiced dialogue recounts the sentiment that kept alive the rebellious spirit of prisoners who, from within, have fought and continue to fight so that there can be no place for prison in this society. Today, as states plan a future of “more prisons for ever more people,” and from Latin America to Greece, passing through Italy and France, they attempt to bury hundreds of comrades along with their experiences of struggle, we believe that the answer is the multiplication and diffusion of the attack against the State and Capital not just from one front, but from many.

In this sense, the recovery of past experiences, besides bringing them out of the oblivion in which the State wants to bury them, contributes to keeping them alive in a perspective of insurrectionary struggle, placing “prison within an organic relational fabric,” not considering it “as a thing apart, an isolated entity detached from the rest of the world, from society, and from us. If we only see it as a fortress, it will remain impregnable. […] Prison is the structure where the concept of punishment takes shape, it is the architect who designs it, it is the company that builds it, it is the law that ratifies it, it is the court that introduces it, it is the Carabinieri officer who takes you there, it is the guard who watches over you, it is the priest who holds mass there, it is the psychologist who offers their services. It is this and more. It is the company that exploits the labor of prisoners. It is the one that gets rich by supplying rations, furnishings, control equipment, “luxury” goods that prisoners can buy at a very high price, perhaps doing jobs whose purpose is to reintegrate them into the society of servants and masters. Prison is also the professor who justifies it, it is the reformer who wants it to be more humane, it is the journalist who silences its conditions, it is the citizen who ignores or fears it.”²

The anti-prison struggle, which cannot be relegated to the technical, legal, welfare, or victimistic spheres, must be addressed comprehensively. For this reason, it is necessary to question how to initiate and sustain a permanent conflict against the structures of domination so that repression does not have the strength and ability to isolate and annihilate anyone who refuses to hold their head high, to uphold the necessity of ideas and actions against power.

Alfredo Cospito’s hunger strike, which lasted 6 months, for the abolition of the 41 bis regime for all prisoners against the ostative life sentence was supported by an international solidarity and direct action movement. It highlighted how, starting from the specific demand “Free Alfredo from 41 bis,” it was possible to open a debate and create cracks in the 41 bis and harsh prison system, the apex of the repressive system. This occurred despite living in times that praise disengagement, permanent demobilization, and rampant resignation. The attack on Alfredo was a warning from the State against those who persist in upholding revolutionary ideas and practices—a State that must erase both the possibility and the memory of armed struggle in this country, of which the action against Adinolfi, claimed by Alfredo in court in Genoa, is one of the most recent testimonies. To revisit Alfredo’s hunger strike and the mobilization in his solidarity today, starting from reflections and criticisms that go beyond a broader debate on the 41 bis and repression in Italy, is necessary to reflect on a reality that, while insufficient to seriously challenge the repressive system, certainly ignited some not-so-ordinary sparks. From these, it would be desirable to draw lessons and inspiration for the realization of a project that goes beyond the emergency of the moment and the partiality of the demands. The limitations and critical issues of that mobilization cannot be sidelined. With the end of Alfredo’s strike, it practically stopped, leaving his condition of total isolation unchanged, with nothing to prevent the State from taking its revenge on this comrade, as recent updates on his imprisonment also demonstrate. The return of the GOM officer, previously transferred for his involvement in the “interception scandal,” to the directorship of the 41 bis section of Bancali prison has brought with it a further tightening of already harsh conditions under this regime. Reflecting again on the struggles against the prison system, both inside and out, is therefore necessary so that the experiences recounted in Adíos Prisíon and Kamina Libre can become a tool for action in the present.

¹ Alfredo M. Bonanno, Chiusi a chiave. Una riflessione sul carcere

² Alfredo M. Bonanno, Chiusi a chiave. Una riflessione sul carcere

KAMINA LIBRE:

In 1994, the new High-Security Prison (CAS) was inaugurated in Chile. In this new prison, the democratic system introduced unprecedented measures in the country, even compared to the times of the dictatorship. These measures concerned the control, isolation, and surveillance of inmates and were used for members of existing political-military organizations in Chile. Within this new CAS, which at its peak held over 90 inmates, starting in 1995, on the initiative of a group of prisoners who had broken away from MAPU-LAUTARO, a Marxist-Leninist armed organization, what would later become the Kolektivo Kamina Libre began to form. These comrades began to organize within the CAS, and from 1996 onwards, they also did so through the publication “Libelo,” which would be followed by others such as “Konciencialerta” and “T.I.R.O.” (Radical Organized Insurrectional Transgression). These tools were fundamental in ensuring that the prisoners’ message extended beyond the walls of the CAS. From the mid-1990s, the Kolektivo Kamina Libre began to take shape, declaring itself autonomous, insurrectional, countercultural, and committed to offensive resistance to continue fighting from within, even after the capital’s “democratic transition,” with the clear objective of all its members returning to the streets. This objective was achieved in 2003. The Kolektivo’s positions emphasized the importance of permanent conflict with power, in a phase where other armed organizations were laying down their arms. This confrontation intensified within the prisons: “Riots and hunger strikes constituted the tone of internal mobilizations within the prison for several years, generating dynamism in terms of approaches and initiatives and achieving, on the other hand, gains within the prison, which culminated in the liberation of all members of Kamina Libre. This position reflects the indispensable role that prisoners play in the struggle for their freedom, a position that was also fully in tune with the activity of anti-authoritarians and the struggles in the streets, giving rise to a combative solidarity far removed from the assistentialism and victimhood so common today. They did not wait for more or less conscious people to mobilize for them, but understood that their own freedom depended primarily on themselves, which is why they used their bodies as instruments of struggle during the harsh days of the strikes.”[3]

Starting from the experience of Kamina Libre in Chile, as well as relaunching solidarity with comrade Marcelo Villarroel, still imprisoned today in the jails of the new democratic Chile, we would like to reflect on how external support was fundamental to those who from the inside had first decided to undertake a struggle putting everything at stake, and on how a struggle that began inside a High-Security Prison then extended to the whole of society until the members of the Kolektivo returned to the streets.

[3] Francisco Solar, the Importance of Kamina Libre Today

Starting in 1989, a circular introduced a new section for inmates in Spanish prisons, known as FIES (Fichero de Internos de Especial Seguimiento – File of Inmates Under Special Surveillance). Although this new detention regime was only regulated eight years after its appearance, it was distinguished from the outset by particularly harsh treatment. Initially, the FIES sections were used to confine members of armed gangs, but shortly after, they were extended to all those inmates stubbornly resistant to authority, to conflictive prisoners who, through continuous riots, section fires, or escapes, damaged not only the structures but also the reputation of the prison administration itself. It was thus that the socialist government, then in power, decided to introduce this special detention regime.

“The media, prostituted to power, were given a directive according to which they had to omit everything that happened in Spanish prisons against us, portraying us as psychopaths, with the clear intention of making those methods acceptable to public opinion. They were doing everything to stop the inmates’ complaints, to destroy the APRER association, and to restore order and discipline in prisons through prison terrorism. Those methods had already been used in the past with COPEL. It was about implementing strong pressure aimed at annihilating the mind of the prisoner and demolishing their rebellious spirit, daily bombarding their nervous system until their definitive surrender was achieved.” – Huye Hombre Huye, X. Tarrío

What was experienced in these sections is the result of the paroxysm of punishment, whose real name is torture because the will behind it is the total isolation and absolute annihilation of individuals, both psychologically and physically. They found themselves confined twenty-three hours a day in cells without a bed because mattresses and blankets were confiscated every morning and returned in the evening, without communication with the outside world because every visit from relatives, friends, or lawyers was denied, beaten and handcuffed to the bars for days at the slightest hint of protest. All this happened (as it happens today) not only at the direct hand of the jailer tormentors but also thanks to the help of prison doctors, who induced, if not forced, inmates to take tranquilizers or psychotropic drugs, with the intention of poisoning and sedating them. Mechanisms that aim to make every moment of existence in prison an endless punishment, if not that of naked and raw torture.

The FIES is not the exception within Spanish society, but the most miserably authentic reflection of state morality, in which prison represents the solution to the intrinsic contradictions of this social organization. State morality, the one that “every free citizen” embraces, manifests itself in the cowardice and cynicism of power unconditionally within prisons; all this happens also thanks to those “mercenaries of the prison administration” not represented only by jailers, inspectors, “guarantors” of prisoners, but also by doctors, psychiatrists, social workers, etc., who allow its functioning and normalization inside and outside the squalid prison walls. An Italian equivalent of the Spanish FIES can be considered the 41 Bis: the prison regime wanted by the infamous General Dalla Chiesa at the time of the struggle carried out by the Italian State against the Mafia organizations; it was then used for members of revolutionary organizations, and for some years its grip has also extended to anarchists, as happened to comrade Alfredo Cospito, who is currently still in total isolation.

The book Adíos Prisíon (Goodbye Prison) was born with the intention of informing and denouncing the detention conditions of the FIES, to raise awareness among those outside about the real condition of the inmates, to incite protests, rebellion, and escape. One of the objectives was to break the isolation in which they wanted to confine them and to affirm the desire to fight even in the harshest conditions so as not to make prison totalizing on the will of individuals, to attack it to always reaffirm their inalienable desire for freedom. Adíos Prisíon, in this sense, does not recount individual episodes of struggle and escape from prisons; the experiences themselves speak in a choral narrative written by inmates subjected to the FIES.

The book was clandestinely produced in El Dueso prison and its distribution was immediately banned because it “incited escape,” but this censorship did not prevent the book from circulating from cell to cell and from prison to prison, demonstrating once again how vulnerable those walls are. This series of stories is not written with the idea of fantasizing about the exploits of extraordinary individuals, fueling an adventurous imaginary that would put an action movie on the same level as a real escape attempt. What is fundamental and highlighted is a constant tension towards life and the desire for freedom that no darkness of a cell can obscure, that dignity, however offended or weakened, is not something to be negotiated, that despite adversity and torture, the struggle continues together with one’s accomplices. These stories are experiences of challenges to the established power, but also to all those who consider prison the solution to the social contradictions generated by this unjust system.

Starting from this presentation, we would like to discuss the theme of escape not only with respect to its impact on daily prison life, but also on the conditions in which those who escape find themselves, once they have left that monotonous existence and entered the unpredictable state of being on the run. In all this, the contribution of those outside the prison who support the inmates and their struggles in an attempt to extend their revolt beyond the walls, against all the control and repression mechanisms that this society has at its disposal, remains fundamental.